what is the significance of the red guards slogan "to rebel is justified"?

Red Guards (simplified Chinese: 红卫兵; traditional Chinese: 紅衛兵; pinyin: Hóng Wèibīng ) was a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the get-go phase of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.[1] According to a Red Baby-sit leader, the motion's aims were as follows:

Chairman Mao has defined our future every bit an armed revolutionary youth organization.... So if Chairman Mao is our Red-Commander-in-Chief and nosotros are his Red Guards, who can end us? Commencement we volition make China Maoist from within out and so nosotros will help the working people of other countries make the earth scarlet...and so the whole universe.[2]

Despite beingness met with resistance early, the Cerise Guards received personal back up from Mao, and the move rapidly grew. The motility in Beijing culminated during the "Red Baronial" of 1966, which later on spread to other areas in mainland Cathay.[3] [four] Mao made use of the group as propaganda and to accomplish goals such as seizing power and destroying symbols of China'southward pre-communist by ("Four Olds"), including ancient artifacts and gravesites of notable Chinese figures. Moreover, the authorities was very permissive of the Red Guards, and even allowed the Red Guards to inflict bodily damage on people viewed as dissidents. The motility quickly grew out of command, frequently coming into conflict with authority and threatening public security until the authorities made efforts to rein the youths in, with fifty-fifty Mao himself finding the leftist students to have become too radical.[5] The Red Guard groups also suffered from in-fighting every bit factions developed among them. Past the end of 1968, the grouping equally a formal movement had dissolved.

Political slogan by Cherry-red Guards on the campus of Fudan University, Shanghai, Prc says "Defend Primal Committee with (our) blood and life! Defend Chairman Mao with (our) blood and life!"

Origins [edit]

The kickoff students to call themselves "Cherry Guards" in China were from the Tsinghua University Heart School, who were given the name to sign two big-character posters issued on 25 May – 2 June 1966.[half dozen] The students believed that the criticism of the play Hai Rui Dismissed from Office was a political issue and needed greater attending. The grouping of students – led by Zhang Chengzhi at Tsinghua Middle Schoolhouse and Nie Yuanzi at Peking University – originally wrote the posters as a constructive criticism of Tsinghua University and Peking Academy's administrations, who were defendant of harbouring intellectual elitism and conservative tendencies.[vii] Most of the early on Carmine Guards came from the so-called "Five Red Categories".[8] [9]

The Red Guards were denounced as counter-revolutionaries and radicals by the school administration and past fellow students and were forced to secretly encounter amongst the ruins of the Old Summer Palace. Nonetheless, Chairman Mao Zedong ordered that the manifesto of the Scarlet Guards be broadcast on national radio and published in the People's Daily newspaper. This action gave the Scarlet Guards political legitimacy, and student groups quickly began to appear beyond People's republic of china.[10]

Due to the factionalism already emerging in the Red Guard movement, President Liu Shaoqi made the decision in early June 1966 to ship in Chinese Communist Party (CCP) piece of work teams.[6] These workgroups were led past Zhang Chunqiao, head of Communist china's Propaganda Department, in an attempt by the Party to keep the motility under control. Rival Red Guard groups led by the sons and daughters of cadres were formed by these piece of work teams to deflect attacks from those in positions of power towards bourgeois elements in gild, mainly intellectuals.[10] In addition, these Political party-backed rebel groups too attacked students with 'bad' class backgrounds, including children of former landlords and capitalists.[ten] These deportment were all attempts past the CCP to preserve the existing state government and apparatus.[6]

Mao, concerned that these piece of work teams were hindering the class of the Cultural Revolution, dispatched Chen Boda, Jiang Qing, Kang Sheng, and others to bring together the Scarlet Guards and combat the work teams.[vii] In July 1966, Mao ordered the removal of the remaining work teams (confronting the wishes of Liu Shaoqi) and condemned their 'Fifty Days of White Terror'.[11] [ clarification needed ] The Red Guards were then free to organize without the restrictions of the Party and, inside a few weeks, on the encouragement of Mao's supporters, Cherry Guard groups had appeared in almost every school in China.[12]

Chiang Kai-Shek believed Mao lost trust in CCP officials and members, Communist Youth League of Cathay (CYLC) members, and even workers, peasants and soldiers, so he had put faith in the students, and made use of the Red Guards to preserve his authority.[13]

Role in the Cultural Revolution [edit]

Red Baronial and Red Terror [edit]

Mao Zedong expressed personal blessing and support for the Cherry Guards in a letter to Tsinghua University Scarlet Guards on 1 Baronial 1966.[fourteen] During the "Reddish August" of Beijing, Mao gave the motion a public heave at a massive rally on eighteen Baronial at Tiananmen Square. Mao appeared atop Tiananmen wearing an olive green military uniform, the type favored past Carmine Guards, but which he had non worn in many years.[14] He personally greeted 1,500 Cherry-red Guards and waved to 800,000 Red Guards and onlookers below.[14] A large number of members of "Five Black Categories" were persecuted and even killed.[3] [4]

The rally was led by Chen Boda and Lin Biao gave a keynote speech.[14] Red Guard leaders, led past Nie Yuanzi, also gave speeches.[14] A high school Red Guard leader, Song Binbin placed a red armband inscribed with the characters for "Carmine Guard" on the chairman, who stood for half dozen hours.[14] The viii-18 Rally, as it was known, was the first of eight receptions the Chairman gave to Scarlet Guards in Tiananmen in the fall of 1966. Information technology was this rally that signified the beginning of the Red Guards' involvement in implementing the aims of the Cultural Revolution.[fifteen]

A second rally, held on 31 August, was led by Kang Sheng and Lin Biao also donned a red arm band. The last rally was held on 26 November 1966. In all, the Chairman greeted eleven to twelve meg Red Guards, near of whom traveled from afar to nourish the rallies[fourteen] [16] including one held on National Day 1966, which included the usual ceremonious-military parade.

Attacks upon the "4 Olds" [edit]

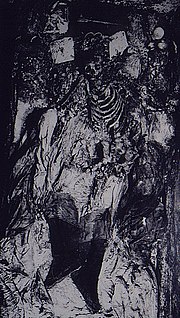

The remains of Ming dynasty Wanli Emperor at the Ming tombs. Cherry-red Guards dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and Empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously "denounced" and burned.[17]

In August 1966, the 11th Plenum of the CCP Central Committee had ratified the 'Sixteen Articles', a document that stated the aims of the Cultural Revolution and the role students would exist asked to play in the motility. Afterwards the 18 August rally, the Cultural Revolution Group directed the Red Guards to attack the 'Four Olds' of Chinese lodge (i.eastward., sometime customs, former civilization, old habits, and former ideas). For the rest of the year, Red Guards marched across People's republic of china in a campaign to eradicate the 'Iv Olds'. Old books and fine art were destroyed, museums were ransacked, and streets were renamed with new revolutionary names, adorned with pictures and the sayings of Mao.[18] Many famous temples, shrines, and other heritage sites in Beijing were attacked.[nineteen]

The Cemetery of Confucius was attacked in November 1966 by a team of Ruddy Guards from Beijing Normal University, led by Tan Houlan.[twenty] [21] The corpse of the 76th-generation Duke Yansheng was removed from its grave and hung naked from a tree in front end of the palace during the desecration of the cemetery.[22]

Attacks on other cultural and historic sites occurred betwixt 1966 and 1967. One of the greater damages was to the Ming Dynasty Tomb of the Wanli Emperor in which his and the empress' corpses, forth with a multifariousness of artifacts from the tomb, were destroyed by student members of the Cherry-red Guard. Between the assaults on Wan Li and Confucius' tombs alone, more than than vi,618 celebrated Chinese artifacts were destroyed in the want to achieve the goals of the Cultural Revolution.[23]

Individual property was likewise targeted by Ruddy Guard members if it was considered to correspond one of the Iv Olds. Commonly, religious texts and figures would be confiscated and burned. In other instances, items of historic importance would be left in identify, simply defaced, with examples such as Qin Dynasty scrolls having their writings partially removed, and stone and wood carvings having the faces and words carved out of them.

Re-education came alongside the destruction of previous culture and history, throughout the Cultural Revolution schools were a target of Red Baby-sit groups to teach both the new ideas of the Cultural Revolution; also equally to point out what ideas represented the previous era idealizing the Four Olds. For case, one student, Mo Bo, described a variety of the Red Guards activities taken to teach the adjacent generation what was no longer the norms.[24] This was done co-ordinate to Bo with wall posters lining the walls of schools pointing out workers who undertook "bourgeois" lifestyles. These actions inspired other students beyond Red china to join the Ruddy Guard as well. One of these very people, Rae Yang, described how these deportment inspired students. Through say-so figures, such as teachers, using their positions as a form of accented control rather than equally educators, gave students a reason to believe Red Guard messages.[25] In Yang's case information technology is exemplified through a teacher using a poorly phrased statement equally an excuse to shame a student to legitimize the instructor's ain position.

Attacks on civilization rapidly descended into attacks on people. Ignoring guidelines in the 'Sixteen Articles' which stipulated that persuasion rather than force were to exist used to bring about the Cultural Revolution, officials in positions of authority and perceived 'bourgeois elements' were denounced and suffered physical and psychological attacks.[18] On 22 August 1966, a central directive was issued to cease constabulary intervention in Red Guard activities.[26] Those in the law who defied this notice were labeled "counter-revolutionaries." Mao's praise for rebellion finer endorsed the actions of the Red Guards, which grew increasingly violent.[27]

Public security in Mainland china deteriorated rapidly every bit a issue of central officials lifting restraints on trigger-happy beliefs.[28] Xie Fuzhi, the national police primary, said information technology was "no big deal" if Red Guards were beating "bad people" to death.[29] The law relayed Xie's remarks to the Red Guards and they acted accordingly.[29] In the course of nigh 2 weeks, the violence left some 100 teachers, school officials, and educated cadres dead in Beijing's western district lonely. The number injured was "too large to be calculated."[28]

The most gruesome aspects of the campaign included numerous incidents of torture, murder, and public humiliation. Many people who were targets of 'struggle' could no longer behave the stress and committed suicide. In August and September 1966, there were 1,772 people murdered in Beijing lonely. In Shanghai there were 704 suicides and 534 deaths related to the Cultural Revolution in September. In Wuhan in that location were 62 suicides and 32 murders during the aforementioned period.[xxx]

Intellectuals were to suffer the brunt of these attacks. Many were ousted from official posts such every bit university teaching, and allocated manual tasks such as "sweeping courtyards, building walls and cleaning toilets from 7am to 5pm" which would encourage them to dwell on past "mistakes."[31] An official report in October 1966 stated that the Crimson Guards had already arrested 22,000 'counterrevolutionaries'.[32]

The Ruby-red Guards were also tasked with rooting out 'backer roaders' (those with supposed 'right-wing' views) in positions of authority. This search was to extend to the very highest echelons of the CCP, with many summit party officials, such every bit Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping and Peng Dehuai, beingness attacked both verbally and physically by the Blood-red Guards.[33] Liu Shaoqi was especially targeted, every bit he had taken Mao'southward seat every bit State Chairman (Chinese President) following the Great Bound Forward. Although Mao stepped down from his post as a sign of accepting responsibleness, he was angered that Liu could take the reins of mainland china.

Clashes with the PLA [edit]

The Cherry-red Guards were not completely unchallenged. The Red Guards were non permitted to enter Zhongnanhai, the Forbidden City, or any armed services facility that was tasked with classified information (i.e. special intelligence, Nuclear Weapons development). Several times, Ruby Guards attempted to storm Zhongnanhai and the 8341 Special Regiment, which was responsible for Mao'south security, fired upon them.[34]

Jiang Qing promoted the idea that the Crimson Guards should "crush the PLA,"[ citation needed ] with Lin Biao seemingly supportive of her plans (e.yard., permitting Blood-red Guards to boodle barracks). At the same fourth dimension, several military commanders, oblivious to the ongoing chaos that the People's Liberation Army (PLA) had to deal with, disregarded their chain of command and attacked Crimson Guards whenever their bases or people were threatened. When Red Guards entered factories and other areas of production, they encountered resistance in the course of worker and peasant groups who were nifty to maintain the status quo.[34] In add-on, there were bitter divisions within the Cherry-red Guard motility itself, especially along social and political lines. The most radical students often found themselves in disharmonize with more conservative Cherry-red Guards.[16]

The leadership in Beijing also simultaneously tried to restrain and encourage the Red Guards, adding defoliation to an already chaotic situation. On the one paw, the Cultural Revolution Group reiterated calls for non-violence. On the other hand, the PLA was told to assist the Carmine Guards with transport and lodging, and assist in organizing rallies.[xvi] By the end of 1966, about of the Cultural Revolution Group were of the stance that the Red Guards had go a political liability.[16] The entrada against 'capitalist-roaders' had led to anarchy, the Red Guards' actions had led to conservatism amongst China's workers, and the lack of discipline and the factionalism in the movement had fabricated the Red Guards politically unsafe.[35] 1967 would run into the decision to dispel the student movement.

Factionalism within the Red Guards [edit]

"Enveloped in a trance of excitement and alter," all student Cherry Guards pledged their loyalty to Chairman Mao Zedong.[1] Many worshipped Mao to a higher place everything and this was typical of a "pure and innocent generation," especially of a generation that was brought up under a marxist party, which discouraged religion altogether.[36] Excited youths took inspiration from Mao's often vaguely open-ended pronouncements, generally believing the inherent sanctity of his words and making serious efforts to effigy out what they meant.[ citation needed ]

Factions rapidly formed based on individual interpretations of Mao's statements. All groups pledged loyalty to Mao and claimed to accept his best interests in listen, nevertheless they continually engaged in verbal and physical skirmishes throughout the Cultural Revolution, proving that at that place was no core political foundation at work. This domestic chaos continued until the second one-half of the Cultural Revolution, when the 9th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Political party started civil policies.[ citation needed ]

Youths from families with political party-members and of revolutionary origin joined conservative factions. These factions focused on the socio-political condition quo, keeping within their localities and working to challenge existing distributions of ability and privilege.[37] Those from the countryside and without ties to the CCP ofttimes joined radical groups who sought to change and uproot local authorities leadership.[38]

The chief goal of the radicals was to restructure existing systems of inequality to do good those of poorer backgrounds,[ dubious ] as the supposed capitalist roaders who were corrupting the Socialist agenda. Primarily influenced by travel and a freer exchange of ideas from different regions of Cathay, more joined the radical, rebel factions of the Cherry-red Guards by the 2d half of the Cultural Revolution.[38]

Some historians, such equally Andrew Walder, argue that individuals and their political choices also influenced the development of Cherry-red Baby-sit factions across China. Interests of individuals, interactions with authorization figures, and social interactions all altered identities to forge factions that would fight for new grievances against "the system".[37]

Suppression by the PLA (1967–1968) [edit]

Past Feb 1967, political opinion at the centre had decided on the removal of the Carmine Guards from the Cultural Revolution scene in the interest of stability.[39] The PLA forcibly suppressed the more than radical Reddish Guard groups in Sichuan, Anhui, Hunan, Fujian, and Hubei provinces in Feb and March. Students were ordered to return to schools; student radicalism was branded 'counterrevolutionary' and banned.[forty] These groups, as well as many of their supporters, were later on branded May Sixteenth elements after an ultra-left Red Guard organization based in Beijing.

May Sixteenth elements (五一六分子) were named subsequently the so-called May Sixteenth Army Corps (五一六兵团; 1967–1968), ultra-left Ruby Guards in Beijing during the early years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) who targeted Zhou Enlai with the backing of Jiang Qing. The name came from the historic May 16 Observe (五一六通知) which Mao Zedong partially wrote and edited, which triggered the revolution. However, Mao was concerned with its radicalism, so in tardily 1967 the group was outlawed on conspiracy and anarchism charges, followed by the arrest of almost Cultural Revolution Grouping members (except Jiang Qing). A nationwide campaign was later launched to liquidate "May Sixteenth Elements", which ironically created more chaos and chaos.

Endless innocent people were accused of being "May Sixteenth elements" and ruthlessly persecuted. According to one source, in the province of Jiangsu alone, more than 130,000 "May Sixteenth elements" were "ferreted out" and more than 6000 either died or suffered permanent injuries.

There was a wide backlash in the spring against the suppression, with student attacks on any symbol of authorization and PLA units, simply not on Marshal Lin Biao, the Minister of National Defense and i of the Chairman's biggest allies. An order from Mao, the Cultural Revolution Grouping, the Country Council, and the Fundamental Military Affairs Committee of the PLA on 5 September 1967 instructed the PLA to restore society to China and finish the anarchy.[41] The order came inside months of incidents of PLA forces disobeying regime and CRG orders during the summertime (including the Wuhan incident), the aftermath of these resulted in even more than violence amid the Blood-red Guards, fifty-fifty targeting local level PLA formations, raising fears of a repeat of the Wuhan events and other like ones.

The PLA violently put down the national Cerise Guard movement in the year that followed, with the suppression oft brutal. A radical alliance of Red Guard groups in Hunan province, called the Sheng Wu Lien, was involved in clashes with local PLA units, for case, and in the showtime half of 1968 was forcibly suppressed.[42] At the same time the PLA carried out mass executions of Red Guards in Guangxi province that were unprecedented in the Cultural Revolution.[42]

The final remnants of the movement were defeated in Beijing in the summer of 1968. Reportedly, in an audience of the Red Baby-sit leaders with Mao, the Chairman informed them gently of the end of the movement with a tear in his eye. The repression of the students by the PLA was not as gentle.[43] Later the summer of 1968 some more than-radical students continued to travel beyond China and play an unofficial part in the Cultural Revolution, merely by and then the motion'southward official and substantial role was over.

Rustication [edit]

From 1962 to 1979, 16 to eighteen million youths were sent to the countryside to undergo re-instruction.[44] [45]

Sending city students to the countryside was also used to defuse the student fanaticism set up in move by the Red Guards. On 22 December 1968, Chairman Mao directed the People'southward Daily to publish a piece entitled "Nosotros too take two hands, let us not laze almost in the city", which quoted Mao as saying "The intellectual youth must get to the country, and exist educated from living in rural poverty." In 1969 many youths were rusticated.[46]

Historiography [edit]

The Carmine Guards and the wider Cultural Revolution are a sensitive and heavily censored chapter in the history of People's Democracy of China. Official government mentions of the era are rare and brief.[47]

In popular civilisation [edit]

- Allen Ginsberg refers to "Reddish Guards battling land workers in Nanking" in the start line of his poem "Returning North of Vortex," included in the drove The Fall of America: Poems of These States (1973).

- The Carmine Guard (1967), a Nick Carter spy novel, features scenes involving Red Guards in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution.

- In the volume Son of the Revolution (1983), the protagonist, Liang Heng, becomes a Red Guard at age 12, despite the years of persecution he and his family received from them.

- In The Last Emperor (1987), the Red Guard appeared nearly the end of the pic humiliating the prison warden who treated the Emperor of China, Puyi, kindly.

- Nien Cheng's memoir Life and Death in Shanghai (1987) describes Red Baby-sit activities in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution.

- Jung Chang's autobiography, Wild Swans (1991), describes the atrocities committed past the Red Guards.

- In Goodbye My Concubine (1993), the Ruby Guards humiliate Cheng Dieyi and Duan Xiaolou as they try to overthrow the old society.

- In the film The Blue Kite (1993), Tei Tou's classmates are shown wearing the ruby-red ribbons of the ruddy guards, and the film ends with the ruby-red guards denouncing his stepfather.

- The film To Live (1994) has the Scarlet Guards appearing in a few scenes, showing their various types of activity.

- In the short The Red Violin, the eponymous violin is hurriedly subconscious under the flooring boards of a firm. The Reddish Guards come up, intermission in and forcibly confiscate the (empty) case and burn it. The violin survives, hidden, to keep its Odyssey.

- In Hong Kong, TVB and ATV often depicted the brutality of the Red Guards in films and television dramas. They are rarely portrayed in film and television programs produced in mainland China.

- The video game Command & Conquer: Generals misleadingly named the Chinese standard infantry unit the "Red Guard" which ensured the game's ban in Communist china.[ citation needed ]

- Ji-li Jiang's Red Scarf Daughter (1997) is a novel about the Cultural Revolution that prominently features the Red Guards. The protagonist oftentimes wishes she could become one.

- In his autobiography Gang of One, Fan Shen provides kickoff hand accounts of his youth as a Scarlet Guard.

- Li Cunxin makes repeated reference to the Red Guards in his autobiography, Mao's Last Dancer (2003).

- In the book Ruby Bloom of China, Zhai Zhenhua recounts her time as a Crimson Guard.

- Yang Rae recounts her time in the Red Guards and in the countryside in Spider Eaters.

- In the novel Frog past Mo Yan, Carmine Guard is mentioned on several occasions, similar public prosecution.

- Members of the Ruddy Baby-sit are featured prominently in the novel The Three-Trunk Problem by the Chinese novelist Liu Cixin.

- Two American organizations have adopted the championship and ideology of the Cerise Guards in the United States, first being Reddish Guard Party, an Asian-American empowerment organisation and the Carmine Guards, a small American collective of decentralized groups besides inspired past Abimael Guzman, onetime leader of the Shining Path.

- Carmine Guards, and especially Jiang Qing's function in their establishment, are discussed in Adam Curtis's documentary television series Can't Get Y'all Out of My Head.

See also [edit]

- Scarlet August

- Violent Struggle

- Seizure of power (Cultural Revolution)

- Gang of 4

- Morning Lord's day (motion-picture show)

- Kimilsungist-Kimjongilist Youth League

- Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung

- Little Pink, Red ribbon

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Teiwes

- ^ Chong, Woei Lien (2002). Mainland china'south Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: Master Narratives and Post-Mao Counternarratives. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN9780742518742 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Wang, Youqin (2001). "Student Attacks Confronting Teachers: The Revolution of 1966" (PDF). The University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b Jian, Guo; Song, Yongyi; Zhou, Yuan (2006). Historical Lexicon of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Scarecrow Press. ISBN978-0-8108-6491-vii. Archived from the original on eleven June 2020. Retrieved x July 2020.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution . The Belknap Press.

- ^ a b c Chesneaux, p. 141

- ^ a b Jiaqi, Yan; Gao Gao (1996). Turbulent Decade: A History of the Cultural Revolution. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 56–64. ISBN0-8248-1695-one.

- ^ Tanigawa, Shinichi (2007). Dynamics of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the Countryside: Shaanxi, 1966–1971. Stanford University. ISBN978-0-549-06376-6.

- ^ Singer, Martin (2020). Educated Youth and the Cultural Revolution in Communist china. University of Michigan Press. ISBN978-0-472-03814-v.

- ^ a b c Meisner, p. 334

- ^ Meisner, p. 335

- ^ Meisner, p. 366

- ^ Kai-Shek, Chiang (nine October 1966). "中華民國五十五年國慶日前夕告中共黨人書" [Manifesto to the CPC Members on the Eve of the National Day of the 55th Years of the Republic of People's republic of china]. 總統蔣公思想言論總集 (in Traditional Chinese). 中正文教基金會 (Chungcheng Cultural and Educational Foundation). Retrieved xi March 2021.

今天很明白的事實,就是毛澤東對於你們這一代,從黨政軍領導幹部到黨員團員及其所謂工農兵群眾,根本上都不敢相信,認為都已不可靠了,所以它不得不寄望下一代無知的孩子們,組訓「紅衛兵」來保衛它個人生命,來保衛它獨夫暴政、生殺予奪的淫威特權。

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 (Chinese)Ni, Tianqi (7 April 2011). "倪天祚, "毛主席八次接见红卫兵的组织工作" 中国共产党新闻网" [Chairman Mao received the organization of the Carmine Guards eight times.]. people.com.cn.

- ^ Van der Sprenkel, p. 455

- ^ a b c d Meisner, p. 340

- ^ Melvin, Shelia (seven September 2011). "Communist china's Reluctant Emperor". New York Times.

- ^ a b Meisner, p. 339

- ^ Joseph Esherick; Paul Pickowicz; Andrew George Walder (2006). The Chinese cultural revolution equally history. Stanford University Press. p. 92. ISBN0-8047-5350-iv.

- ^ Ma, Aiping; Si, Lina; Zhang, Hongfei (2009), "The evolution of cultural tourism: The example of Qufu, the birthplace of Confucius", in Ryan, Chris; Gu, Huimin (eds.), Tourism in Red china: destination, cultures and communities, Routledge advances in tourism, Taylor & Francis US, p. 183, ISBN978-0-415-99189-6

- ^ "Asiaweek article". Asiaweek. 3 January 1984 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jeni Hung (5 April 2003). "Children of Confucius". The Spectator . Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ "Burn, loot and pillage! Destruction of antiques during China's Cultural Revolution". AFC China. 10 February 2013.

- ^ Bo, Lo (April 1987). "I Was a Teenage Red Guard". New Internationalist Magazine.

- ^ Yang, Rae (1997). Spider Eaters. University of California Press. p. 116.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick and Schoenhals, Michael. Mao'due south Last Revolution. Harvard University Printing, 2006. p. 124

- ^ MacFarquhar & Schoenhals; p. 515

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Roderick and Schoenhals, Michael. Mao's Terminal Revolution. Harvard Academy Press, 2006. p. 126

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Roderick and Schoenhals, Michael. Mao's Final Revolution. Harvard University Press, 2006. p. 125

- ^ MacFarquhar & Schoenhals; p. 124

- ^ Howard, p. 169.

- ^ Karnow, p. 209

- ^ Karnow, pp. 232, 244

- ^ a b Meisner, pp. 339–340

- ^ Meisner, p. 341

- ^ Chan

- ^ a b Walder

- ^ a b Chan, p. 143

- ^ Meisner, p. 351

- ^ Meisner, p. 352

- ^ Meisner, p. 357

- ^ a b Meisner, p. 361

- ^ Meisner, p. 362

- ^ Riskin, Carl; United nations Development Programme (2000), Red china man development written report 1999: transition and the land, Oxford University Press, p. 37, ISBN978-0-19-592586-ix

- ^ Bramall, Chris. Industrialization of Rural China, p. 148. Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2007. ISBN 0199275939.

- ^ Shu Jiang Lu, When Huai Flowers Bloom, p .115 ISBN 978-0-7914-7231-half dozen

- ^ Buckley, Chris (13 January 2014). "Bowed and Remorseful, Former Cherry-red Guard Recalls Instructor'due south Death". New York Times.

See likewise [edit]

- Chan, A; 'Children of Mao: Personality Development and Political Activism in the Reddish Guard Generation'; University of Washington Press (1985)

- Chesneaux, J; 'Mainland china: The People's Republic Since 1949'; Harvester Press (1979)

- Howard, R; "Crimson Guards are always right". New Society, 2 February 1967, pp169–70.

- Karnow, S; 'Mao and China: Inside China's Cultural Revolution'; Penguin (1984)

- Meisner, M; 'Mao'due south Prc and After: A History of the People's Republic Since 1949'; Free Press (1986)

- Teiwes, F; "Mao and His Followers". A Disquisitional Introduction to Mao Zedong; Cambridge University Press (2010)

- Van der Sprenkel, Southward; The Ruby Guards in perspective. New Society, 22 September 1966, pp455–6.

- Walder, A; 'Fractured Rebellion: the Beijing Cherry Baby-sit Motion'; Harvard University Press (2009)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Guards

0 Response to "what is the significance of the red guards slogan "to rebel is justified"?"

Enregistrer un commentaire